First a disclaimer. “Third World Country” is in quote marks, because it’s a derogatory term not of my choosing. However, it is the term in most common usage in Argentina, and it is also probably the most relevant to the content that I’m writing in this instance.

I’ve been writing this blog entry for months, so I thought I should just bite the bullet and put it up, even though I’m not really happy with it yet. Think of it as a work in progress. It comes as a result of many conversations that I have had on the idea that “Argentina is a third world country”. I would like to explain why Argentina is not a third world country, and to explore some of the issues around these beliefs.

According to the United Nations

According to the United Nations, Argentina is one of the richest countries in the world. This is calculated using the Human development index which can be found in the United Nations development programme’s Human Development Report 2006. The Human Development Index is a comparative measure of life expectancy, literacy, education, standards of living, well being, and child-welfare. Countries are ranked according to their position in the world where 1 is the highest, currently Norway with an HDI of 0.965, and 177 is the lowest, currently Niger with an HDI of 0.311. As well as an individual rank, countries are also grouped into three broad categories according to high, medium, and low human development.

In 2006 Argentina was ranked 36th in the world with an HDI of 0.863, making it the highest ranked country in Latin America. It is categorised under the high level of human development, along with Chile (HDI 0.859), and Uruguay (0.851), the three Latino countries represented in the highest group. To give an idea in global terms, these countries can be seen on a par with many Eastern European countries, a couple of Gulf states, and several islands in the Caribbean.

According to Paul Samuelson

United-Statesian economist Paul Samuelson proposed a five-category economic model to include the three traditional categories of first, second and third world, plus Japan and Argentina as separate entities on the grounds that neither fitted into any of the three groups. He later revised this theory to four categories; essentially, the rich, the poor, Japan, Argentina, on the grounds that “rich” and “poor” were easy enough to define, but nobody could explain why a country with as few resources as Japan could be so economically successful, nor, conversely, why a country as rich as Argentina could consistently make such a mess of its economy. This tells us that Argentina’s economic past and present, while complex, don’t belong in a “third world” box.

According to Marcos Aguinis

In “el atroz encantó de ser argentinos”, Cordoban essayist Aguinis explores the paradoxes that have shaped the culture and economy of Argentina over the last hundred years or so. The very name Argentina comes from the Latin for “silver”, and a hundred years ago Argentina was the seventh richest economy in the world. However even at that time, paradoxes were observed and commented on by outsiders. Aguinis quotes Mexican comic Mario Moreno as saying “Argentina is comprised of millions of inhabitants who want to bankrupt it, although they haven’t yet succeeded”, and French administrator Gastón Jeze in “The public finances of the Argentinian republic”, concluded that “there exists a profound and radical contrast between the economic prosperity, and the disorder of the public finances”.

According to Freire

Grass roots educator Paulo Freire is best known for his work among the oppressed in Brazil of the early 1960’s. However, it was his later experience in Harvard, USA which changed his opinions considerably. Here Freire discovered that issues of poverty – in both material and human forms; repression, exclusion and powerlessness, exist in very diverse communities: the ‘third world’ exists within the ‘first world’ and the struggle for liberation in both is essentially the same. Although the UK and the USA are considered to be ‘successful’ economies by established standards, both also display wide disparities of wealth and opportunity. Thus from Freire’s experience in the USA he extended his definition of the Third World from a geographical to a political concept. In Freire’s language therefore, a “Third World Country” would be a false concept, since the Third World relates to the person’s experience of exclusion, rather than their current location.

According to Hollywood

Argentina comes off quite badly when compared with Hollywood. In Hollywood everyone is tall, good looking, rich, has straight teeth, and never goes to the toilet or gets sick. Naturally the facts are slightly different. The diversity of experience which surprised Freire in the 1960’s is little different in many respects today. In the USA there are over 46 million US citizens without medical insurance (Kaiser Commission Jan 2007) and uninsured children in the USA who are admitted to hospital are twice as likely to die as their insured counterparts (Families USA, March 2007). That means that there are more people in the USA without access to adequate health care than the total population of Argentina. Likewise I have had various discussions with people here who are adamant that there cannot possibly be any homelessness in the UK. The reality is that Shelter works with 170,000 homeless and vulnerably housed people every year in the UK. We of “The West” have a lot to answer for in terms of the images that we peddle of ourselves.

“How do you explain why Argentina’s public services aren’t any better if we are not a Third World Country?” Because however badly Argentina seems to be doing, at this moment there are nearly two hundred other countries who are faring worse, and the thirty or so who appear to be doing better aren’t as perfect as their Hollywood image suggests either.

Welcome to the real world

The other side of the coin is that the reason why the Hollywood image peddles so successfully is because people want to buy it. If someone else has managed to be tall, good looking, rich, with straight teeth and never need to go to the toilet, then maybe I can too. If I perceive myself to be poor and you to be rich, then you hold the solution to my problems. If I have none of the answers and you have all of the answers, then all I need is access to your answers. Accepting that I am richer than I think I am, and that you are less perfect than I think you are, means accepting the possibility that there might not be any answers after all, for any of us, and thus living with the reality that this world could never be as God intended it to be, and that Christ really is our only hope. And that’s a brave decision.

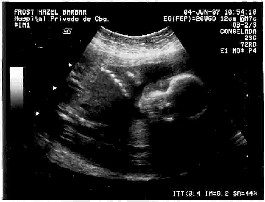

This baby has a lot to answer for, I had to take my bike in to the shop this week, and have my beloved racing-handlebars swopped for some upright ones because I can’t reach down to the brakes any more, which was starting to feel like a bit of a safety hazard for doing business with Cordoban drivers! So now I’m in “granny-sit up and beg” mode, but at least it means I can keep cycling for a while longer, hadn’t anticipated that consequence to my increasing fatness. I’ve also just bought a pair of dungarees, after completely running out of clothes that fit me.

This baby has a lot to answer for, I had to take my bike in to the shop this week, and have my beloved racing-handlebars swopped for some upright ones because I can’t reach down to the brakes any more, which was starting to feel like a bit of a safety hazard for doing business with Cordoban drivers! So now I’m in “granny-sit up and beg” mode, but at least it means I can keep cycling for a while longer, hadn’t anticipated that consequence to my increasing fatness. I’ve also just bought a pair of dungarees, after completely running out of clothes that fit me.

I know, this is one of those “I believe it’s a baby because you tell me it is” sort of grainy black and white pics, which if we’re honest looks quite a lot like a bean, but really could be just about anything. This particular bean is ours, taken this morning. Almost definitely male, he is currently at four and a half months, with all limbs and vital organs in residence. This picture is his face, on the grounds that it is probably the one he will be the least embarrassed by when he’s fifteen.

I know, this is one of those “I believe it’s a baby because you tell me it is” sort of grainy black and white pics, which if we’re honest looks quite a lot like a bean, but really could be just about anything. This particular bean is ours, taken this morning. Almost definitely male, he is currently at four and a half months, with all limbs and vital organs in residence. This picture is his face, on the grounds that it is probably the one he will be the least embarrassed by when he’s fifteen.